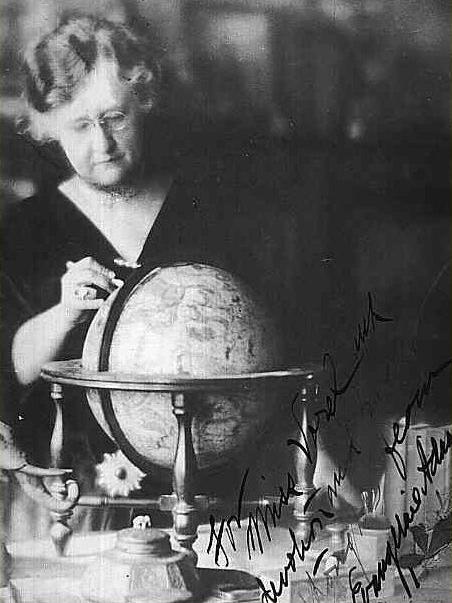

Arrested after a sting operation conducted by a special all-women police task force, Evangeline Adams, “the world’s most famous astrologer,” stood trial for the crime of fortune-telling on December 11, 1914. This was not the first or the last time Evangeline Adams would face judgement for her craft, but this trial marks a turning point in American legal thought and was intended to set a precedent for cases against astrologers. Evangeline Adams wasn’t the only one on trial, astrology itself was.

The Stars on Trial: Evangeline Adams and the Legal Fate of Fortune Telling

Famed Astrologer Evangeline Adams

Written by Elizabeth Srsic | October 17, 2025

SAVANNAH, GA - Born on All Hallow’s Eve, Juliette Gordon Low’s family said that, when she was a little girl, she loved learning about and adhering to superstitions and folklore. It comes as no surprise that Juliette also visited fortune-tellers and astrologers to gain insight into the future. Today, only one artifact of these visits exists: a horoscope read by celebrity astrologer Evangeline Adams. The line between fortune-telling and astrology has always been difficult to legally define, and not long after Juliette received her reading, Evangeline Adams would distinguish herself as a leading force in the debate.

Women on trial for “occult” practices conjures imagery of witchcraft persecutions and violent ends before angry mobs. As late as 1951, if a person (likely a woman) was on trial for fortune-telling, palmistry, seances, or other Spiritualist practices, while living in England, Ontario, or other British colonies, they could have been tried under the 1736 Witchcraft Act, which repealed the prior laws and punishments and imposed fines and imprisonment instead. In 1736, during the Enlightenment Era, witchcraft and magical powers were already considered laughable. Even though the Witchcraft Act was still applicable, by 1824, fortune-tellers were generally tried under the Vagrancy Act which punished, in addition to people with unstable housing, “every person pretending or professing to tell fortunes, or using any subtle craft, means, or device, by palmistry or otherwise, to deceive and impose on any of his Majesty’s subjects…”

In the United States, fortune-tellers and Spiritualists found themselves subject to laws, which varied state-by-state, jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction, but had nearly identical wording to the English Vagrancy Act. New York Code of Criminal Procedure, Section 899, classified fortune-tellers and Spiritualists as “disorderly persons” and defines a fortune-teller as someone who “pretends to tell fortunes.” This classification begs the question of how to prove one is pretending and how to avoid infringing upon freedom of religion. According to American lawyer and legal pioneer, Blewett Lee, in an article written for the Columbia Law Review 1922 in the United States, unlike in England, “[t]here is no particular public demand in the United States for their punishment…Every conviction, however justifiable, starts up a cloud of apologists and defenders, and spiritualism gets good advertisement,” and fortune-tellers were excellent advertisers.

A New York Times article from December 12, 1909, claims that there are “One Thousand Fortune Tellers Plying Their Trade in New York City” and according to Dolan Cochran during a lecture at the Tenement Museum, 1,000 is undercounting. Most of these 1,000+ fortune tellers advertised their services either through newspaper ads, fliers, or pamphlets. In an 1895 survey of fortune teller advertisements published in The Journal of American Folklore, Henry Carrington Bolton, chemist and scholar, lists the most common services offered by fortune tellers and clairvoyants and how they marketed themselves to an eager public.

“To add to the mystery which is supposed to surround the lives of these gifted mortals, they claim to be of Egyptian ancestry, ‘gypsy queens,’ ‘born with cauls,’ and the ‘seventh daughter of a seventh daughter,’ a happy domestic accident supposed to confer miraculous powers upon the younger women. And to still further excite curiosity and to stimulate superstitious belief, the advertisers adopt fanciful names, often indicative of foreign births…”

Evangeline Adams, however, felt no need to utilize the image of exotic ancestry or supernatural symbolism to promote her trade. Instead of donning robes or headdresses and conducting business from dimly lit rooms, Adams rented office space in Carnegie Hall, hired secretaries, readily explained her background as a researcher, and claimed to be a descendant of John Adams; in other words, a well-educated, upper-middle class, professional, all-American woman. According to her defense lawyer during trial, “… [her office] was a simple apartment with library furniture without signs of any kind in or about the studio, except to indicate that it was the office of the defendant.” From these offices, she offered her services as an astrologer both in-person or by mail for a cost-prohibitive fee of $10. Her clients, including Juliette Gordon Low, were from respectable circles, a fact she often cited in publications, giving her another layer of credibility. This was the image of the “scientific” astrologer Adams presented at court in 1914. Putting astrology on trial wasn’t the aim of the prosecution or the judge, it was Adams’ plan to finally, publicly, legitimize her practice once and for all.

The People ex rel. Adele D. Priess v. Evangeline S. Adams was overseen by Judge John J. Freschi, a New York City magistrate with the assistant district attorney representing the prosecution. Evangeline Adams’ arrest was a part of a large-scale effort by the New York City Police targeting people who “pretend to tell fortunes,” and it was those words that Judge Freschi cites as one of the primary considerations of the case.

“The practice of astrology is, in my opinion, but incidental to the whole case and as bearing only on the question of the good faith of the defendant, as I will point out later. The statue provides that persons who pretend to tell fortunes shall be adjudged disorderly persons and punished as prescribed therein."

At the outset of the trial, Judge Freschi isn’t interested in astrology, but by the conclusion will claim that Adams raises the practice to “the dignity of an exact science.”

The trial began with the testimony of Adele D. Priess, the undercover agent working for the Detective Bureau of the New York Police. She described in detail a visit to Adams’ offices at Carnegie Hall on May 13, 1914. Priess explained how Adams took a piece of paper, drew a circle on it, and divided the circle into sections, occasionally checking a book and adding notes to the drawing as the interview continued. Adams also read Priess’ palm, drew charts for Priess’ children, and intimated potential future outcomes. At face value, Priess’ testimony is enough to secure a conviction. Another judge may not have pursued the matter further, but Judge Freschi observed:

“There is a conflict, however, on material points of the case between the prosecuting witness and the defendant’s version of what happened. The complainant admits that she cannot remember every word of the interview, which lasted, according to her best recollection, about thirty-five minutes. Yet it took the complainant only five minutes to narrate what she claims was said by both parties. The defendant, on the other hand, claims that the interview lasted more than hour; and it is obviously fair to assume that the complainant did not fully and fairly present all the facts I the case."

Judge Freschi is quick to point out that he is not questioning the legitimacy or motive of Priess, he is simply observing that her testimony of an event from over half a year prior, which lasted for only a fraction of the supposed length of the initial encounter, could not be complete. Now, it was Evangeline Adams’ turn to take the stand for a lengthy cross examination, and she came prepared. In her autobiography, Adams sets the scene: “I had gone into that court room with a pile of reference books that reached nearly to the ceiling and a mass of evidence that reached as far back as the Babylonian seers.” While the prosecution’s case relied only on the testimony of one person, Adams’ defense was crafted using the testimony of mathematics, astronomy, and research.

When questioned about the palm reading, Adams said, “I told her that is she would always go by her first impression, what Wall Street men called ‘hunches’ she would be quite fortunate in speculation.” In her sessions, communications, advertisements, and interviews, Evangeline Adams chose her words with precision and invoking Wall Street during the trial was a part of her careful strategy. In the years leading up to the trial, the field of economics as we understand it today was relatively new and came about during a period of rapid, frequent recessions and financial uncertainty. In 1905, when the Supreme Court made a ruling regarding financial speculation and forecasts, they were “ruling not only over financial matters, but over who got to forecast the future, and how,” and concluded that “[p]eople will endeavor to forecast the future, and to make agreements according to their prophecy. Speculation of this kind by competent men is the self-adjustment of society to the probable.”

Economic forecasters, an emerging profession, were the “competent prophet[s]” that the Supreme Court deemed worthy of foretelling the future. Economists began to shift how we conceptualized economic disasters. Instead of “chaotic, externally imposed events” disasters like the Panic of 1907 were “components of regular fluctuations in business cycles.” The practice was embedded into business and government through the circulation of “data analyses, charts, and models through private forecasting agencies, newsletters, and weekly newspaper bulletins, to convince the public that there were patterns in economic phenomena, and thus that they were predictable and worth taking chances on.” Strategically and similarly, Evangeline Adams legitimized astrology through the use of data, charts, and numerous publications that mirrored the efforts of economists, which she supplied to the court as evidence in her defense. To further legitimize her practice, it was a widely publicized “fact” that Evangeline Adams’ clients included J.P. Morgan, Charles Schwab, and two presidents of the New York Stock Exchange.

After Adams’ testimony, her lawyer further emphasized the scientific nature of astrology, calling astrology “mathematical or exact,” “empirical,” and “the oldest science in existence. It is not only pre-historic but pre-traditional, and must not be classed with fortune telling…” citing the Encyclopedia Britannica’s definition of natural astrology to drive the point home. An authoritative receptacle of knowledge like the Encyclopedia Britannica was on Adams’ side, who could argue that her astrology was not legitimate? Not Judge Freschi who declared that “[t]he defendant has given ample proof that she is a woman of learning and culture, and one who is very well versed in astronomy and other sciences.” Although Judge Freschi praises Evangeline Adams for her professionalism and the scientific nature of her deductions, he also makes clear in his ruling that all cases regarding fortune telling must be case-by-case and that his decision is not to be unilaterally applied to all fortune telling trials. “Every fortune-teller is a violator of the law; but every astrologer is not a fortune-teller.” And with that, Evangeline Adams was acquitted and astrology legitimized in the eyes of the law and the press.

On December 14, 1914, just a few days after the trial, The Evening World ran a feature article titled “Astrology More Certain in Its Diagnosis Than Medicine or Law, Says Miss Adams,” which included eye-catching illustrations and an exclusive interview with Adams. “What I hope to do, now that Magistrate Freschi’s decision has help clear the way, is to found an Astrological Research Society… I want to bring together so many proofs of the authenticity of astrological deduction that the science must be accepted for what it really is – a source of knowledge to which all may appeal for assistance...” Adams’ efforts to legitimize astrology had only just begun. She had a vision for the future and a pathway forward that just might have been written in the stars.

Research Sources

Adams, Evangeline, The Bowl of Heaven. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1926.

Beaumont, Matthew. “Socialism and Occultism at the ‘Fin de Siècle’: Elective Affinities.” Victorian Review 36, no. 1 (2010): 217–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41039117.

Board of Trade v. Christie Grain & Stock Co., 198 U.S. 236 (1905)

Bolton, Henry Carrington. “Fortune-Telling in America To-Day. A Study of Advertisements.” The Journal of American Folklore 8, no. 31 (1895): 299–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/532745.

Cochran, Dolan, and Grace McGookey. “Mystics in Manhattan.” Virtual Tenement Tour. Lecture presented at the Virtual Tenement Tour: Mystics in Manhattan, October 29, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GaOTWtMHZw&t=372s.

Cordery, Stacy A. Juliette Gordon Low: The Remarkable Founder of the Girl Scouts. New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2012.

Evangeline Adams. “Evangeline S. Adams Scientific Astrology.” New York Tribune. New York, September 25, 1909.

Friedman, Walter A. Fortune Tellers: The Story of America’s First Economic Forecasters. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Gomel, Elana. “‘Spirits in the Material World’: Spiritualism and Identity in the ‘Fin De Siècle.’” Victorian Literature and Culture 35, no. 1 (2007): 189–213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40347131.

Levine, Nick. “The Dignity of an Exact Science: Evangeline Adams, Astrology, and the Professions of the Probable, 1890-1940.” Thesis, Yale, 2014. https://hshm.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/2014-levine.pdf.

Lee, Blewett. “The Fortune-Teller.” Virginia Law Review 9, no. 4 (1923): 249–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/1064993.

Lee, Blewett. “Spiritualism and Crime.” Columbia Law Review 22, no. 5 (1922): 439–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1112490.

Low, Juliette Gordon, 1860-1927. "Horoscope of Juliette Gordon Low. Compiled by Evangeline S. Adams." 1860/1927. September 12, 2025. https://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/juliettegordonlow/do:318-15-170.

Marshall, Marguerite Mooers. “Astrology More Certain in Its Diagnosis Than Medicine or Law, Says Miss Adams.” The Evening World. December 14, 1914.

Moore, R. Laurence. “The Spiritualist Medium: A Study of Female Professionalism in Victorian America.” American Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1975): 200–221. https://doi.org/10.2307/2712342.

Morrisson, Mark S. “The Periodical Culture of the Occult Revival: Esoteric Wisdom, Modernity and Counter-Public Spheres.” Journal of Modern Literature 31, no. 2 (2007): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30053265.

New York State Senate. Laws of New York. Fortune telling Penal (PEN) Chapter 40, Part 3, Title J, Article 165 § 165.35 Fortune telling. 2014-09-22. Accessed 9-22-2025. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PEN/165.35

People ex rel. Priess v. Adams, Court Listener (New York City Magistrates’ Court 1914). https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/6252544/people-ex-rel-priess-v-adams/.

Polland, Dr. Annie, and Edward Portnoy. “Clairvoyant Housewives of the Lower East Side.” Tenement Talk. Lecture presented at the Tenement Talk: Clairvoyant Housewives of the Lower East Side, n.d. October 25, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gGrPNtjtZtI.

“To-Day’s Radio Program.” The New York Herald. August 25, 1922, Vol. LXXXVI No. 360 edition.

UK Parliament §. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/religion/overview/witchcraft/.

Vagrancy Act 1824 c.83 (Regnal. 5_Geo_4) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo4/5/83.

Young, Jeremy C. “Empowering Passivity: Women Spiritualists, Houdini, and the 1926 Fortune Telling Hearing.” Journal of Social History 48, no. 2 (2014): 341–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43306017.